As a little girl, Carmelita could only dream of learning to read and write. One of fourteen children, she had responsibilities in the household from an early age. She took care of younger siblings and sold handicrafts to tourists on the streets. There were no resources, time, or hope for sending her to school. Watching her dream for education slowly fade as she grew up, she hoped that her own children one day would be afforded the opportunity.

Next generation

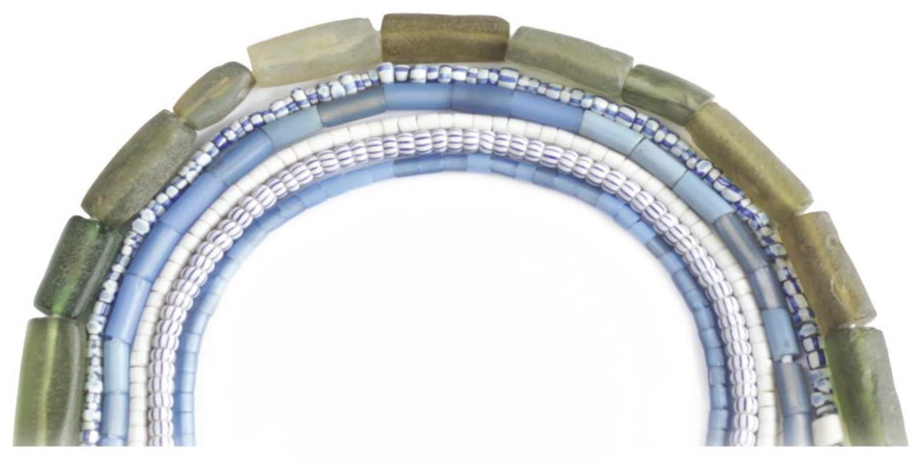

When she was old enough, her sister taught her how to weave seed beads into jewelry. Her skills and dedication paid off as she successfully traded these delicate creations in the subsequent years. So much so, that she has been able to support all six of her children through high school! Seeing them established in the professional careers they studied for is her pride and joy.

Serendipity

A kind foreigner whom she met while selling on the street one day, heard of her childhood dream and connected her with a tutor. This is how, at age 33, Carmelita was finally taught to read and write. This experience emboldened her to enroll in primary school, and eventually, she finished sixth grade along with the twelve-year-old students.

Rainbows, flowers, trees

Inspired by the dramatic beauty and vivid colors of nature around her Guatemalan village, she designs and crafts intricate pieces, which you can view and buy here: bracelets, rings, chokers, badge holders, and eyeglass holders. What she appreciates about modern times are the technological advances that made communication much easier between her and the customers. Because Carmelita delights in getting orders and filling them on time! Finding the right colors for specific orders is sometimes a challenge. A challenge she doggedly accepts. She says her husband is her greatest support.

Faith seeds

And now Carmelita has a new dream: she wants to buy a car. Reality check: the percentage of car owners in Guatemala’s population is the same as the percentage of the US population who do not own cars (8%). In other words, this is a big ambition! Her children smile and tease her, but she has seen a few preposterous dreams dusted off and come to life already. The little seed beads strung into jewelry are called “mostacillas”, a word related to “mostaza”, which is Spanish for “mustard.” This reminds me of the familiar “faith like a mustard seed” challenge. With her sincere and indefatigable trust, I daresay she will yet see mountains move!

.jpeg)

.

.