We weave in and out of traffic. Stories are experiences woven together. Long hair, baskets, and dough are braided. Knitting and crocheting are basically weaving with yarns.

But when we speak about weaving here, it's in the context of textiles, the interlacing of fibrous threads to create fabric. Every piece of clothing on your body is woven fabric. The sheets you sleep on, bath towels and dishtowels, rugs, curtains, table linens. Living as we do in the modern age, most of us are oblivious to the intricate processes involved in manufacturing the items we daily use and enjoy.

Fabric is one such article commonly utilized and taken for granted.

Imagine yourself in 6000 BC, in need of a blanket or shirt. After planting and harvesting, you spin natural fibers like cotton or flax into threads. Or you twist sheared sheep wool or manipulate silkworms to obtain yarn. If you are feeling creative, you dye some of the threads with plant or insect extracts in order to incorporate a design in the weaving. For the next few days or weeks, you patiently insert the transverse weft yarn over and under the tightly stretched lengthwise warp yarn. Back and forth. Painstakingly slow. Mesmerizingly meditative.

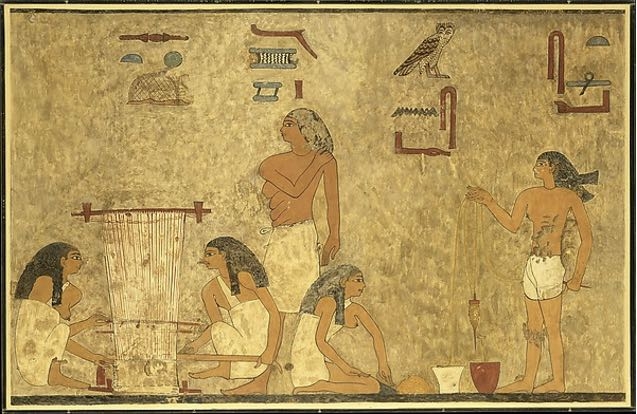

Due to the use of fragile organic materials, we have no samples of these early woven pieces, as we do of ancient pottery shards. Tombs in Egypt unveiled fragments of woven textile, preserved in the dry climate of the sandy desert, as well as a 5000-year-old terracotta plate depicting women weaving on a vertical loom.

The basic need for cover meant that a loom featured prominently in households everywhere, and the skill was passed on to each new generation. As an art form woven pieces also communicated cultural values, traditions, and personal emblems. The care, skill, and time it took to create a weaving enhanced its value, affording extra income or means of trade. Weaving remained the unique product of time-consuming manual operation for centuries.

Similar to what happened with most “cottage industries” during the Industrial Revolution, the demand for mass production required the mechanization of looms. Thus, in 1786, the first power loom was introduced. This machine enabled a faster weaving process and larger output but came with certain limitations. One important feature, the weaving of complicated designs and textured fabric, remained a manual operation.

Until

Several decades later, French entrepreneur JM Jacquard, built an attachment to the loom that used interchangeable perforated cards to guide the warp threads automatically. A desired pattern could be woven by simply changing the cards, effectively automatizing even complex weaving.

An English inventor, Charles Babbage, adopted the idea of punch cards in 1837 to store programs in his “Analytical Engine”, a proposed general-purpose computer. Mathematician Ada Lovelace recognized the symbol-manipulating potential of Babbage’s computational machine. "We may say most aptly that the Analytical Engine weaves algebraic patterns just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves," she noted. Before the same century ended, an American inventor designed a tabulating machine to input data for the 1890 US Census. Punch cards were used in digital computing for close to another 100 years until electronic devices replaced them.

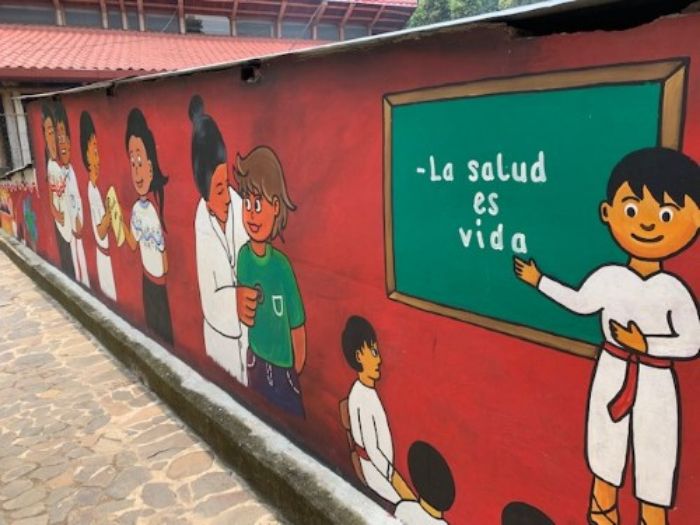

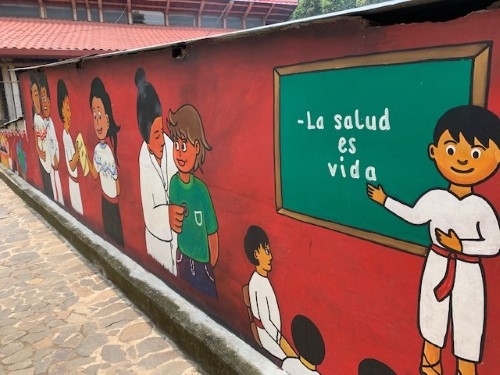

Mayan weaving

While punch cards and antique looms populate museum exhibits in fast-paced modern societies, manual weaving is still widely practiced as it has been for millennia in many cultures. In these places, everyday garments and house linens are still exclusively made with fabric woven on traditional looms.

The rhythmic sound of the wooden treadle

The muted thud of reed against breast beam

The soft claps of hands shaping tortillas

The daily symphony in a Mayan household.

As part of their traditional outfit, the Mayan women of Guatemala wear a skirt known as a “corte”. It is similar to a wrap-around skirt, except three times as much fabric is involved. It is generally the work of men to weave the 7-meter-long piece on bulky treadle looms. In dressing, the women wrap the fabric around, around, and around the lower half of the body and secure it with a decorative girdle. The final ensemble resembles a long, straight pencil skirt, which you can imagine being very restrictive. Till you encounter the same women in traditional dress on a steep mountain trail: sure-footed, graceful, and confident like a mountain goat!

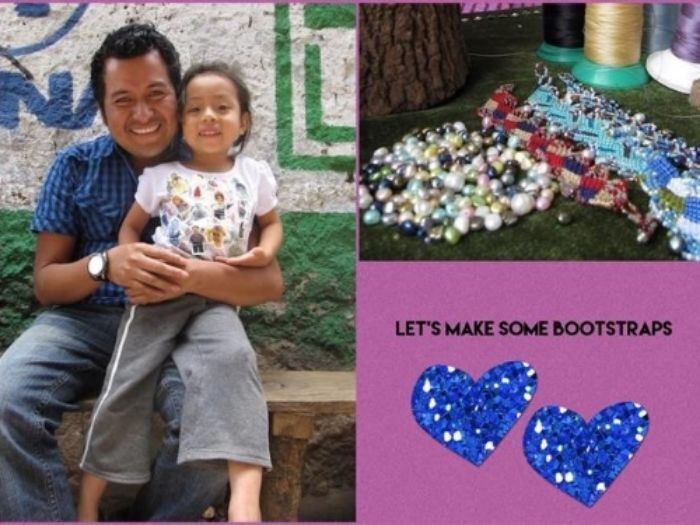

The quality of these woven skirts is undeniable. Even used and discarded pieces are highly valued and repurposed. If you think of the hours that went into handwoven textiles, prolonging their lifespan in every possible format is a way to honor the ancient craft of weaving.

Here are some of our unique re-creations of Mayan "corte":

Sustainable Corte overalls Buy here

Explorer bag from repurposed corte Buy here

Corte turned Tourist Bag! Buy here

Keep up with what “looms ahead” in the textile world.

More on the history of weaving: https://www.artemorbida.com/brief-history-of-weaving/?lang=en

To see the fascinating connection between weaving and algorithms: https://bricklayer.org/weaving/

The artist Ahree Lee, in an exhibit called Pattern:Code, connects the history of women in crafts to their role in computing. Worth a look here: https://www.fastcompany.com/90425067/weaving-coding-and-the-secret-history-of-womens-work

_700.jpeg)

_700.jpeg)

.

.